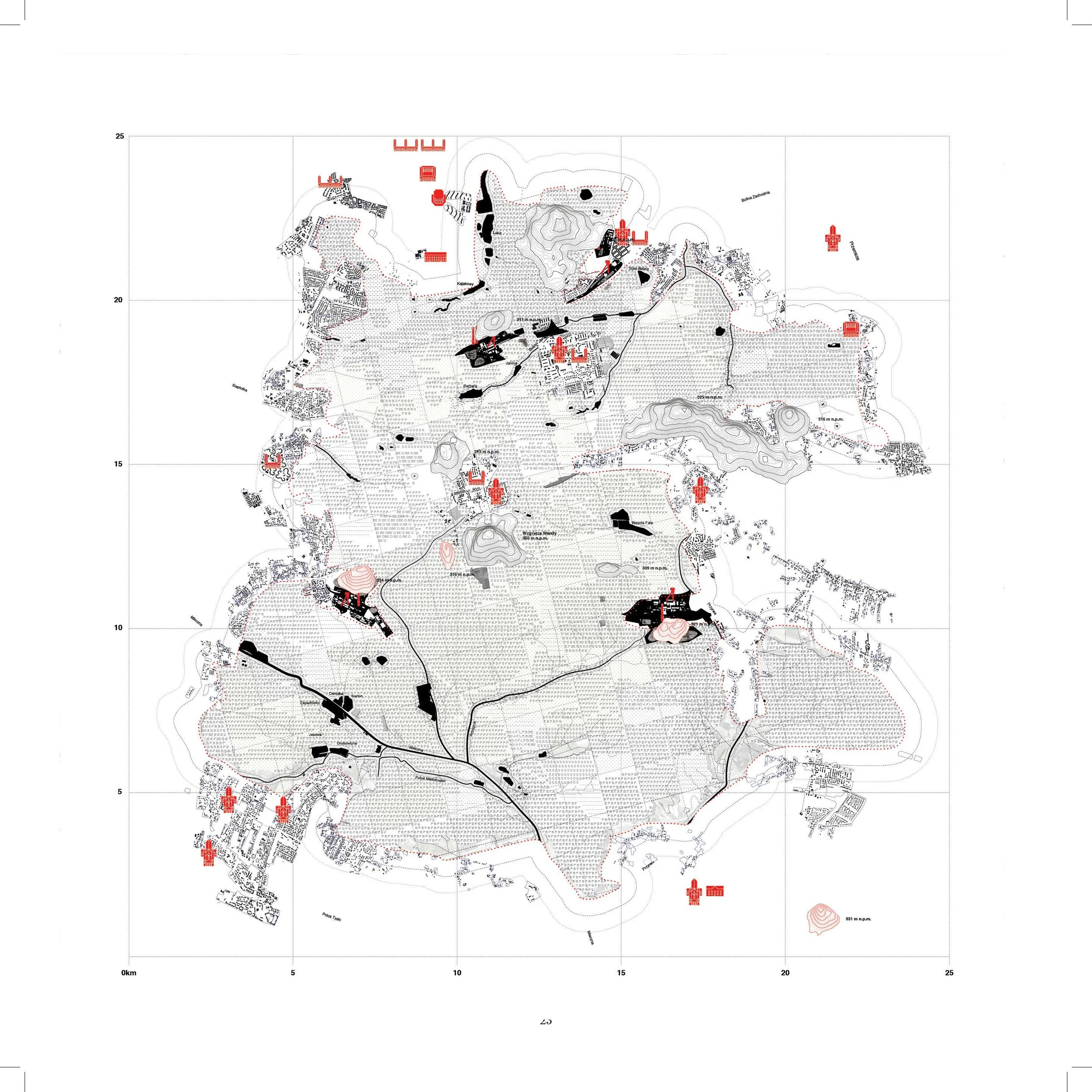

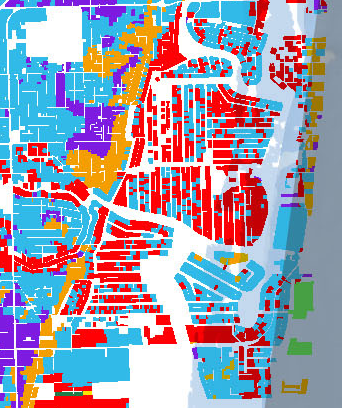

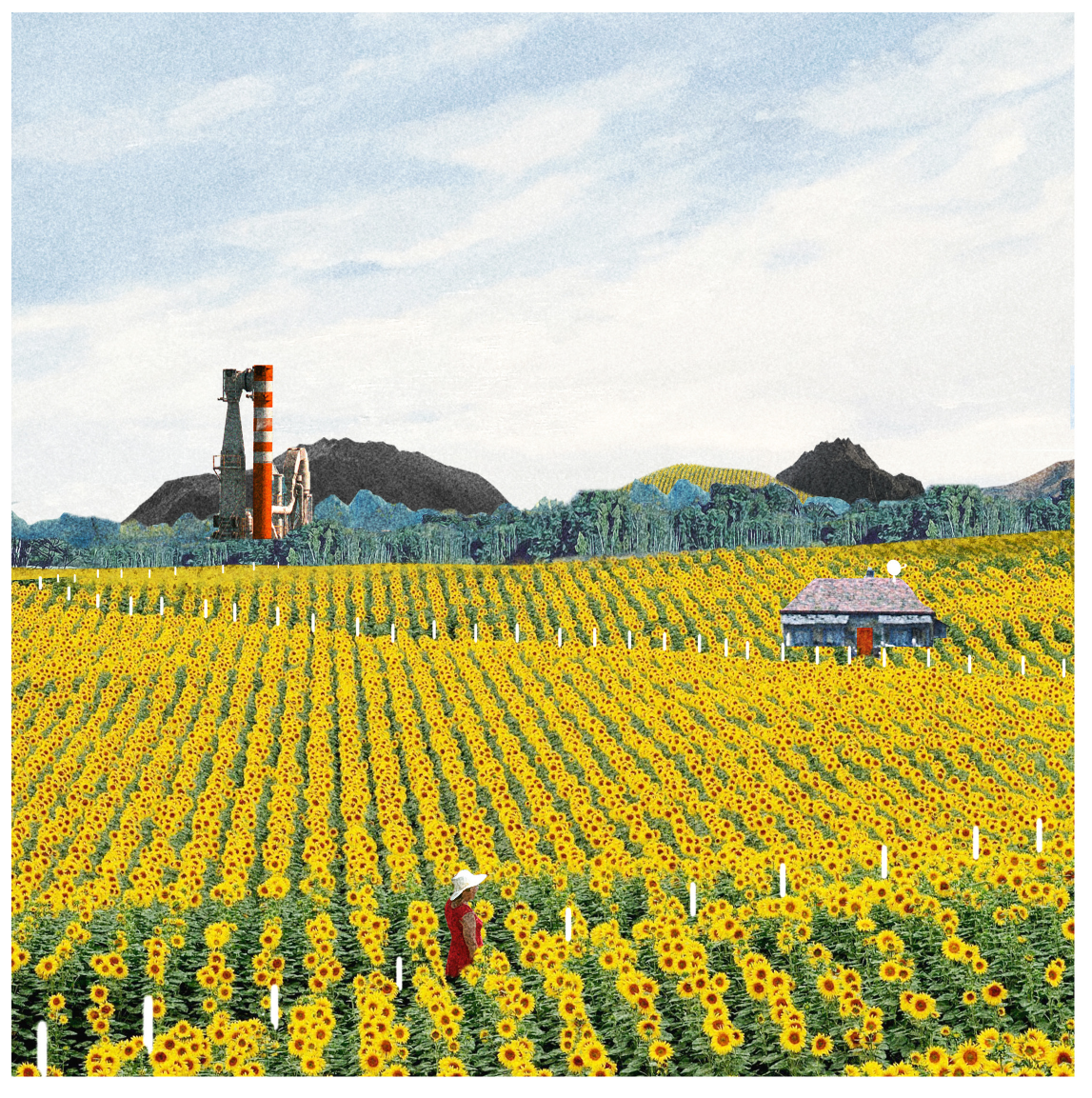

Chelsea, MA is an industrial waterfront town near Boston, MA. As a predominantly minority and predominantly industrial city, Chelsea is faced with a host of environmental problems, stemming from years of industrial activity that have polluted the water and the air. Essential transportation networks such as highway 1 and the T line provide access between other metropolitan cities in the area and Boston’s city center, but they cut Chelsea into disparate parts, impacting connectivity and fragmenting the urban fabric. West Chelsea, which also includes parts of the neighboring town of Everett, is located in the area to the West of Highway 1, and bears the brunt of this industrial legacy. A host of scattered industrial elements include the Mystic Power Plant, Distrigas Oil and Gas Storage the New England Produce Center, and other light and medium industrial and commercial functions, all of which share this space with public institutions such as hospitals and schools. These industrial functions all have priority access to the Chelsea Creek and Mystic River fronts, disconnecting residents of the city from one of their most essential assets: the water. But access to this water also has its own risks. This industrial area is the most vulnerable to sea level rise and pluvial flooding, located in the infill of the historic Island’s End Creek. Without proper attention, this area faces serious flooding hazards. But rather than reduce Chelsea’s coastline with a barrier at the entrance to Island End’s Creek, as many resiliency initiatives may suggest, we pose a different question: what if we expand the coastline, and invite the water in? To determine the extent of floodable area, we identified three pieces of critical infrastructure: the New England Produce Center, the T LINE commuter rail, and Everett Avenue. To protect these three critical areas, we propose returning a large-low lying swath of Industrial land to coastal use and creating a multi-functional berm which emphasizes connections between the now protected and floodable sides of the city. Protecting these three pieces of infrastructure results in positive externalities. Over time, the floodable area can be transformed into a coastal wetland, a green space that provides recreational and leisure opportunities for residents and visitors alike. Unlike other berms, we believe this strategy describes a new urban condition we call 'bermanism'. 'Bermanism' is “the utilization of a berm not to protect as much land as possible, but as a strategic marker which differentiates areas of upzoning (increased urban intensity) with areas of downzoning (return to green space and recreational use). As a marker, the berm functions as the primary access point by which floodable areas are connected to those that are protected by its existence. This process of upzoning and downzoning support four critical hingepoints along the berm; creating opportunities for new functions and integrated programming between floodable and protected. Together, these components form a cohesive whole, connected by the berm, where before there were only scattered elements. Together, they create a new form of urbanism which dramatically improves the quality of life in Chelsea.

With Mario Giampieri, Juncheng Yang, and Yue Wu